18 Mar Imagining a stellar future for our students

How do you plan for an uncertain future during a time of rupture? Woodstock Principal Dr Craig Cook shares the challenges of strategic planning which has to imagine everything students will need to make a positive different to the world (or worlds) for the rest of their lives.

Back in January, we sent our key stakeholders – including parents, staff, StuCo members and alumni – details of the strategic planning process which is currently under way for Woodstock School. Thanks to all of you who took the time to complete the survey, and especially to those of you who volunteered to be part of this process in some way. One of the key outcomes of this exercise, besides giving a clear direction for the next years of Woodstock School, is that we get to hear the clearly articulated voices of our wider community.

When formulating any long-term plan, the biggest challenge is trying to envision one’s imagined future. There is no crystal ball, and the events of last year have demonstrated how the best laid plans need to be flexible enough to adapt if the circumstances demand it. Second-guessing what the future holds is difficult enough for any organisation, but in education there are additional levels of complexity. When we plan for the next five years, our vision must extend over a far longer timescale. What, as educators, do we need to do to prepare our students to be equipped to thrive not just in 2026, but for the rest of their lives? What social and environmental challenges will they face, how will working practices change, and what will students need to become agents of positive change in the world? When we look at the next 50 years or more, so much of this is beyond the event horizon that it’s impossible to pre-empt all the hard skills they will need in the future. Yet it is our role to envisage what they will need to flourish, whatever the world brings their way.

In March of last year, I shared an analogy describing the disruption caused by Covid-19 as a metaphorical blizzard, and that when the sky clears the world will have fundamentally changed in its wake. At the time we were only a few weeks into the pandemic, and nearly a year later we still don’t know what its consequences will be and how deep the layers of change will go. We can however surmise that many of these changes will be positive. It may be that in fact the ‘blizzard whiteout’ conditions haven’t hindered our vision, but have instead provided a moment of clarity, when we have been forced to stop doing things one way, only to realise that another way proves to be more effective – whether it be cost, in efficiency or in environmental sustainability. We’ve incrementally slipped into this way of living since the agrarian revolution, hundreds of years ago, and haven’t had a chance to collectively pause for breath and wonder if there is indeed another way.

I’m not talking about education and schooling here – I think it’s fair to say that the desire for children to return to school is shared universally. If anything, the pandemic has demonstrated how crucial the in-person element is as the foundation of schooling. But in other areas, there are some who don’t want a return to normal, who enjoy the increased flexibility of the last year and are happy to do without the daily commute and work travel. Companies are realizing the cost savings they can make by reducing office space in prime locations, as well as the benefits of a satisfied workforce and enhanced productivity. Tech giants, Twitter and Facebook have announced that their staff can now opt to work from home permanently. It’s a fair bet that what they do today, many others will follow in the not too distant future. If enough do, the outcome may include urban decentralization and transport networks freed of the daily movement of millions, reduced pollution and a levelling of property markets as location demands less of a premium.

We owe it to our current and future students to not just imagine what we know is possible, but to contemplate the seemingly impossible, and imagine new ways of making it a reality.

Sometimes it takes a major disruption to effect substantial change. Sometimes it takes a major disruptor. Tesla Founder Elon Musk is a controversial figure, but it’s hard to argue that he lacks vision. He was briefly the world’s richest individual earlier this year when shares in his electronic car company rocketed upwards its market value to higher than all the other major car manufacturers globally, combined. Not bad for an Electric Vehicle company delivering fewer the 500,000 cars a year. But it is SpaceX, his rocket and space transportation company, which really has stellar prospects. Musk founded the company in 2002, aiming to reduce the cost of space transportation and travel, with an ultimate goal of colonizing Mars. In November, SpaceX’s Dragon capsule successfully transported four astronauts to the International Space Station, and the company says it’s on track for a first manned mission to Mars in 2026. Musk has said that a self-sustaining city on the planet to be theoretically possible by 2050. Eventually this could be as significant a migration as that caused by the agrarian revolution.

As we put in place the plans for Woodstock School’s future, we could do worse than sharing some of Musk’s ‘black sky thinking’. A student from a hundred years ago would still recognise Woodstock as a school. The tech, outfits and teaching methods have changed, but the basics – teachers and students in the classroom – haven’t. That makes it hard to imagine anything different, but doesn’t mean there is no alternative. We owe it to our current and future students to not just imagine what we know is possible, but to contemplate the seemingly impossible, and imagine new ways of making it a reality.

We are not building a rocket, but today’s Woodstock students could be among those blasting off for the red planet. If this all seems a little far-fetched, you may be interested to know that a former colleague of mine, Dr. Trent Smith, at Simpson University, is working with some of my former students and in partnership with University of California-Davis, exploring how to grow potatoes genetically on Mars, as part of the project to make sustained life there viable. During a time of rupture, no possibility should be seen as too outlandish to rule out, and no horizon should be considered as too far. Perhaps we shouldn’t be preparing students to be global citizens after all?

Dr Craig Cook, Principal

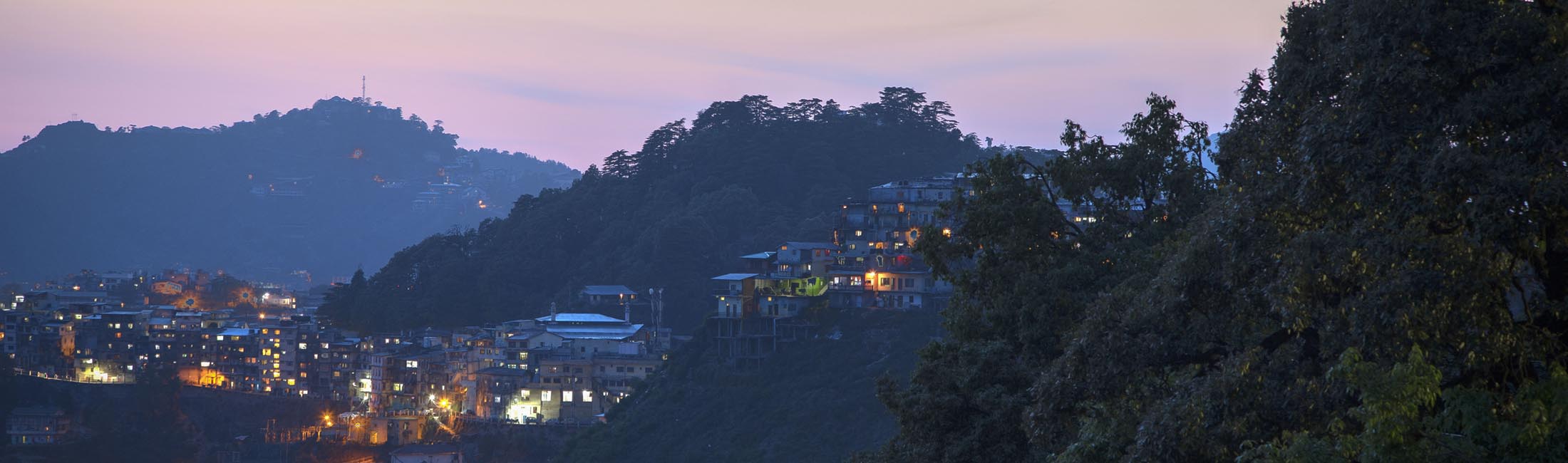

Main photo: Not Mars, but the Spiti Valley can have an otherworldly feel.

No Comments